Looking Back Home: Student Creates Nonprofit to Support the African Town That Raised Him

Emery Ngamasana went home after almost two decades away. What he saw moved him to create a nonprofit that improves the conditions of the rural communities he came from.

Going Home to the Democratic Republic of the Congo after 20 Years

Emery Ngamasana, a Ph.D. student in public health at UNC Charlotte, grew up in Mokala, a rural village in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Mokala, DR Congo

He lived in the cycle of poverty that affects rural communities, but still remembers having a childhood in which his basic needs were met. His mother is an elementary school principal and his father a counselor on the local board of education.

He left his home in 1999 to earn an undergraduate degree in Kinshasa, the country’s capital city, and later a master’s degree in biostatistics in South Africa.

Kinshasa, DR Congo

In 2016, he migrated to the U.S with a green card and worked with UNC Chapel Hill under a grant offered by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In 2018, while working under that funding in West Africa, he revisited his childhood home after almost 20 years of being away.

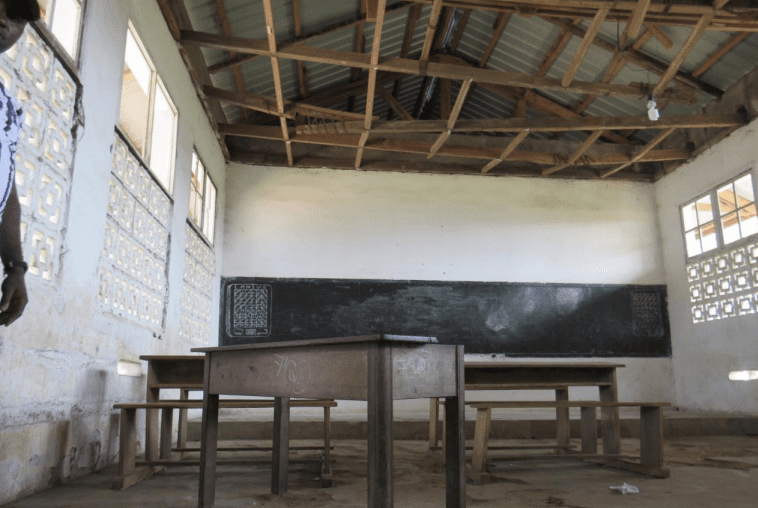

“It brings tears to my eyes,” he said. “I couldn’t believe what I saw. Children went to school barefoot, lacked basic school supplies, and the facilities didn’t have tables and seats. Civil and medical infrastructure had crumbled beyond recognition. Pharmacies, operating beds, and health clinics were in bad shape and roads took hours to traverse if they were not totally impassable.”

Left: Schools lack chairs, tables, and adequate roofing; Right: Hospital bed in a rural health clinic

“In much of the world,” he continued, “living conditions are improving as time goes by, but in my community it is doing the exact opposite.”

What he experienced moved him to form Rural World Impetus (RWI), a nonprofit organization that administers to rural populations in DR Congo.

DR Congo is the 11th largest country in the world by area and 16th by population. Located in central Africa, it features some of the world’s richest natural beauty and biodiversity, including the Congo River and the Congo Rainforest, the 2nd largest river and 2nd largest rainforest in the world after the Amazon.

It has a history of political controversy and systematic underdevelopment resulting from almost a century of European colonial extraction. In spite of its immense natural resources, nearly 75% of its roughly 92 million people are subjected to multidimensional poverty.

Close to 60% of that population is living in rural areas that lack access to healthcare, education, and basic human needs like clean water, sanitation, food, roads, electricity, and housing.

Left: Toilets for maternity patients; Right: local pharmacy

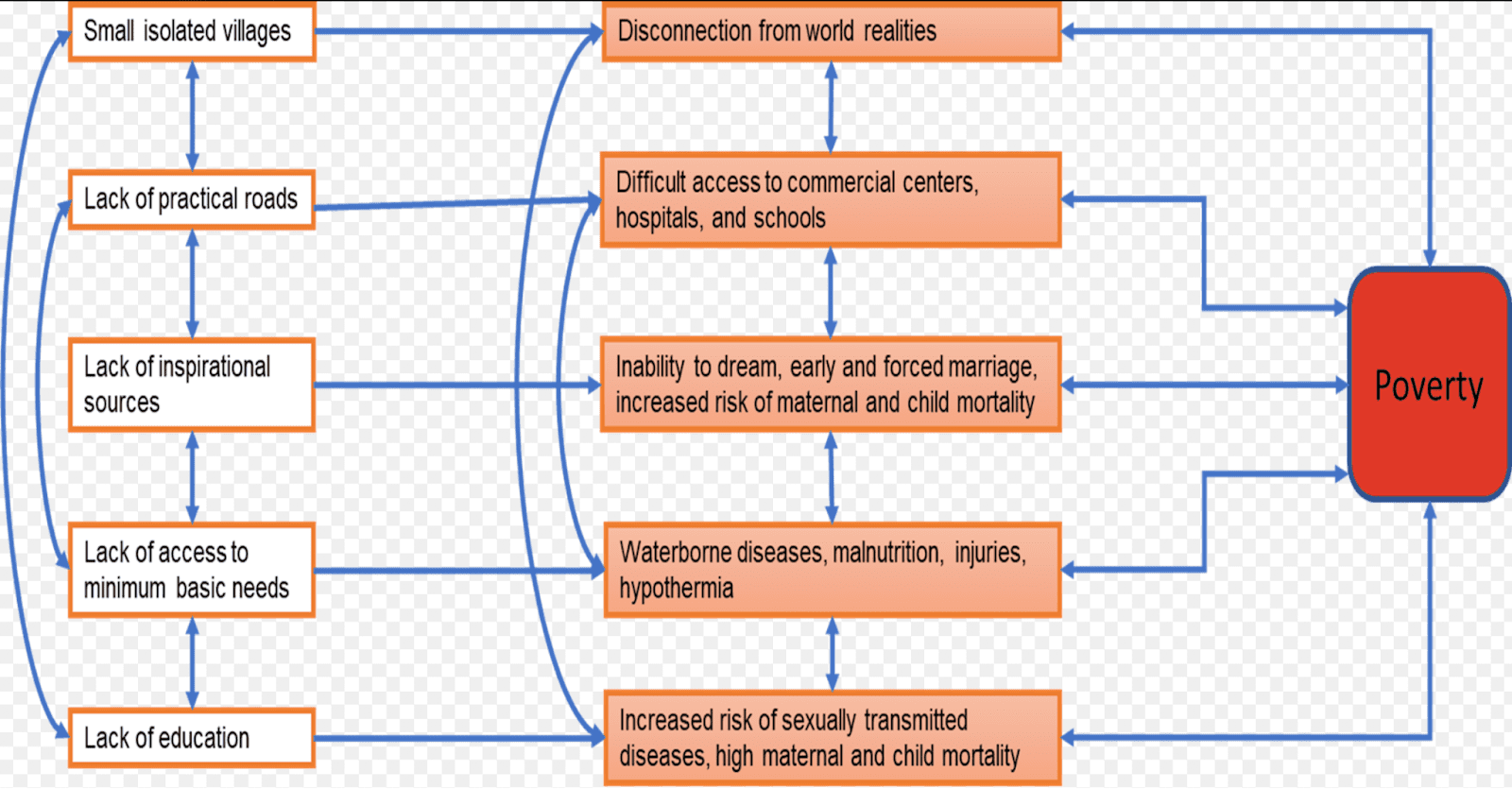

Breaking the Cycle of Poverty

Ngamasana immediately began collecting donations from friends, neighbors and his own household.

“My children have school supplies that we bought for them that they don’t use anymore and are left over,” he said. “And every six months, they outgrow their clothing.”

When he was inundated with requests, he realized he needed to formalize and structure his efforts to maximize his impact, and he started RWI. Its mission is to intervene in the cycles of poverty.

“The problem is,” Ngamasana explained, “that rural parts of the country are caught in cycles of poverty that recreate the conditions that they are born out of. Poor education, absence of public health infrastructure, and economic dependence only produce those same outcomes.”

RWI is a multipronged approach through education, health and public health infrastructure, civil infrastructure and economic self-sufficiency.

First, they acquired a large parcel of land on which they’re working to build a healthcare clinic and walk-in social services facility. The social services facility will provide families in crisis with immediate access to professional social services, including foster care prevention, domestic violence workshops, parenting skills classes, alcoholism and drug abuse treatment and education and family planning.

The healthcare clinic will reduce the prevalence of preventable illnesses through activities and workshops that promote healthy, sanitary, and hygienic environments, focusing on healthy behaviors and overall well-being and positive masculinity to reduce gender-based violence.

Second, they developed a mentorship program.

“The consistent presence of mentors,” Ngamasana explained, “can radically change children’s perception of life and have a positive impact that extends beyond them to the family and the community. Graduates from the program will then become de facto members, thereby ensuring the sustainability of the program beyond the program’s cycle.”

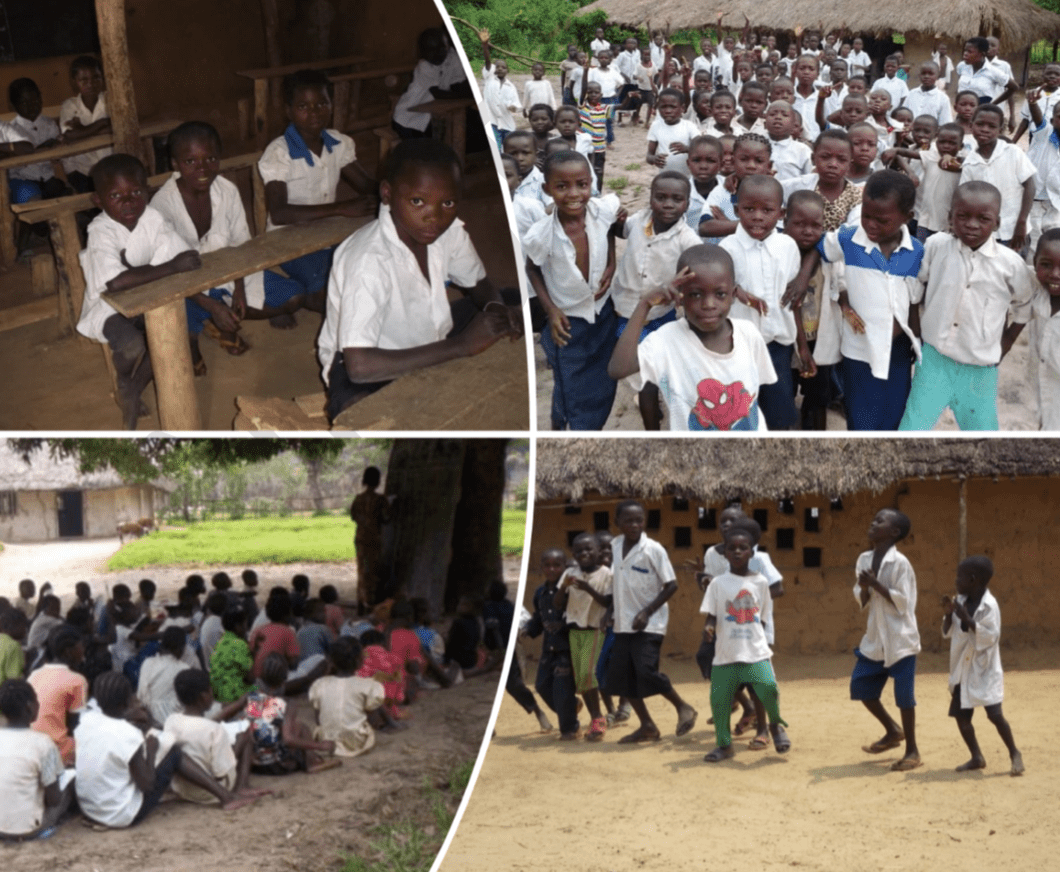

For young girls especially, childhood marriage and pregnancy are major challenges that often lead to premature death due to risk factors for maternal and child mortality. Nearly 53% of girls aged 5 to 17 don’t attend school, but are instead prepared for household tasks.

Ngamasana talks to a 13-year-old who had just given birth

The program is designed to expose children to local champions like doctors, engineers, and economists, as well as provide extracurricular activities that will encourage them to dream. Adapted from the Harlem Children’s Zone Program, they are structured around Peacemakers, STEM education, and Center for Higher Education and Career Support (CHECS).

“We also want to be able to provide those students with exposure to computers so that they can learn, for example, basic programing, standard computer type, Word, and Excel.”

Children attending schools in a rural area in Kimpanga and Lungwama

They have also formed a collaborative through which farmers work together in a unified effort with RWI and fellow producers.

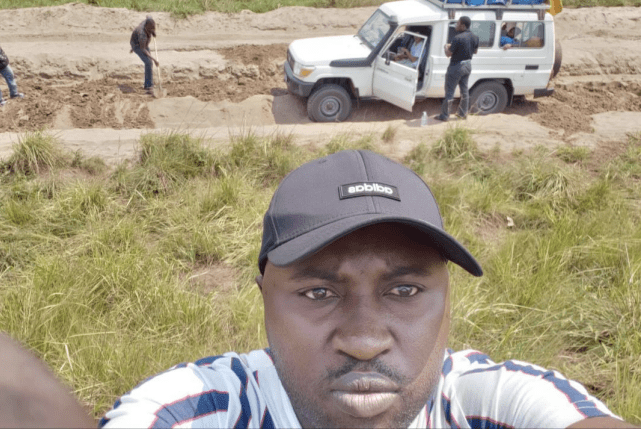

“One of the reasons people remain poor in rural areas is because they lack organization, and when they act individually they cannot afford to transport their products to commercial centers. In addition, small, isolated villages lack access to good roads that connect them. It might take ten days to drive a distance of 60 miles,” Ngamasana said.

Ngamasana’s vehicle gets stuck on poorly-maintained roads

The agricultural cooperative funds local activities, improves education and transportation infrastructure, and pays some percentage towards a community insurance fund, because there is no insurance in rural parts of the country and people pay out of pocket when they get sick. Also, their power to negotiate prices for their product is weak, so a cooperative will help them overcome those challenges and maximize their production capacities.

A Vision for the Future of Health in Africa

“We need more help to expand our efforts,” he said. “We need more donors, volunteers, and community partners. We also need more research. There’s currently no research being done in the rural areas. So, right now, we’re trying to continue to find partners who will come on board and work with us.”

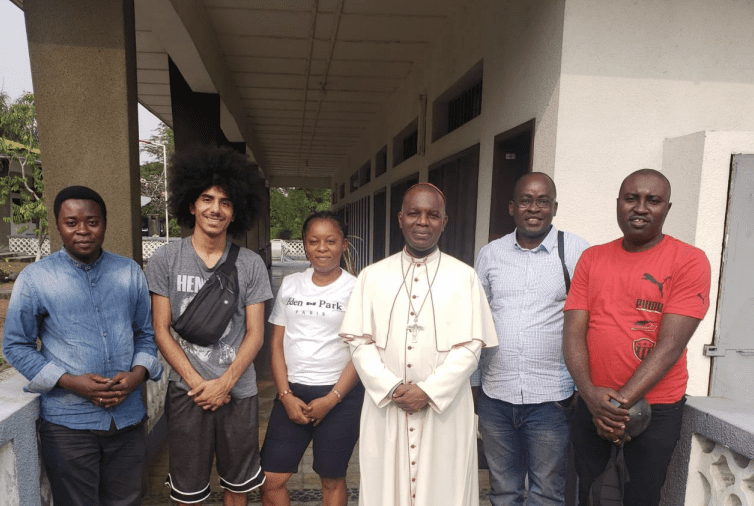

Ngamasana, far right, collaborates with local leaders in DR Congo

During the pandemic, Ngamasana earned a public health certificate at King’s College London, and is now pursuing a Ph.D. in public health at UNC Charlotte. He’s applying his knowledge in biostatistics and public health in his efforts, including planning, assessment, implementation, and social cognitive theories.

When he began speaking publicly about the organization, he began to attract attention. In the audience of one such talk was a doctor who secured medical equipment from Wake Forest Medical School and Novant Health.

“It’s not just about funding, it’s about knowledge. And that’s what’s needed in the future. We need partnership. Anybody that’s interested can come on board. For things like this, having good local partners is essential.”